|

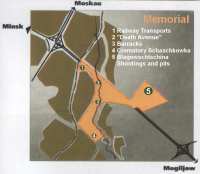

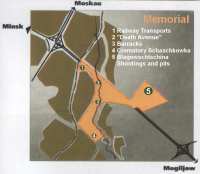

| Camp Map |

In

November 1941, the

Minsk Security Police

and the SD (

Sicherheitsdienst) established a new camp at

the former kolchos (collective farm, 200 hectares / 500 acres) "Karl Marx" in the village of Maly Trostinec,

12 km southeast of

Minsk and 1 km south of

Bolshoi Trostinec village. The camp site had been selected in

September 1941. It measured approximately 200 x 200 m / 4 hectares.

Initially the camp was intended to supply the local Nazi forces with food. In addition a mill, sawmill, locksmith's shop,

joinery, tailoring, shoemakers, asphalt works and other workshops were built. Jews and Soviet POWs

built barracks for around six hundred mainly Jewish slave labourers and their guards.

The prisoners, selected for work in the camp, were kept at first in a large barn and in 20 cellars, which were

formerly used by the local farmers for cooling potatoes, vegetables and meat. Later they were housed in damp

barracks, where bunks were constructed from thick unshaved wooden planks in three tiers. There was no bedding

or mattresses; the people slept on straw.

From

March 1942, the camp was surrounded by a threefold barbed wire fence

(the middle one electrified), and

wooden lookout towers were erected at the corners of the perimeter, which was guarded 24 hours a day. A

guardroom was located close to the entrance to the camp, and a gallows was erected. In

mid-March 1942, partisans

attacked the camp and killed the guards; therefore the Germans increased the total number of guards on 250,

encircled each barrack with a barbed wire fence, posted additional guards around the barracks, installed runways

for dogs, and placed machine-gun nests around the entire site. A subterranean bunker was built, with a tank

standing atop it. Those people who were to be liquidated the next day were held in the bunker.

The 150 men of the camp staff were free to beat, shoot or hang any prisoner without any further authority.

|

| Execution Site Blagowshtchina * |

|

| Memorial Map* |

Like the camps of

Aktion Reinhard, the buildings of Maly Trostinec were

intended to be no more than temporary structures. The camp came to exist for the principal purpose of killing

people and appropriating their few remaining possessions. However, unlike the

Aktion Reinhard camps and

Auschwitz-Birkenau, there were no fixed killing facilities. In this respect,

perhaps the killing site Maly Trostinec most closely resembled in character was

Chelmno, although at Maly Trostinec murder was principally committed by shooting.

Mobile gas chambers (gas vans) only played a subsidiary,

if significant role. Initially, victims were transported to

Minsk, which had

been intended by

Reinhardt Heydrich to

play a more prominent part in the "Final Solution". German reverses on the Eastern front prevented this,

and transports to the East from the

Reich and the "Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia", announced for

January 1942, were cancelled as a consequence.

Operating in a manner similar to that of the death camps of

Aktion Reinhard, the SS men, responsible for

the executions at Maly Trostinec, met the transports arriving at the goods-railway station in

Minsk.

The deported Jews were informed that they would be transferred to houses and estates around

Minsk, but before

this they had to leave their suitcases which would be forwarded by trucks. The Jews had to also leave their

ID-cards, money and valuables for which they received receipts. The victims were completely unaware of their

fate. A group about 20 - 80 specialists were selected from every transport and they were sent to the

Minsk Ghetto

or to the work camp at Maly Trostinec.

Between May 1942 and autumn 1943 the remainder

were taken by trucks directly to the execution site in the

Blagowshtchina forest.

Before they were killed, they had to undress and hand over their valuables. Then they had to march in underwear

to the 60 m long and 3 m deep pits where they were shot in the neck by squads of up to 100

Sipo and

SD-men.

A special group of Russian forced labour workers had to dig out these pits (in winter the pits were created by

detonating dynamite) and fill them up after the killings. Finally, using bulldozers or tractors, the pits

were levelled.

During the unloading of the victims the SS men were very brutal.

To cover the shots and screams while the Jews were killed, music was played from a gramophone, amplified by a

loudspeaker. The population in the neighbouring villages could not hear the executions. Everything was well

organised so that the victims had no time or opportunity for resistance. Each SS man knew his "duty" during

the mass murder, describing the process in detail in post-war trials.

There had been mass executions of local Jews in

Minsk since

August 1941, which continued in and around

the city until the ghetto there was liquidated on

21 October 1943. Beginning on

10 November 1941 with the

arrival of the first transport from the

Reich (990 Jews from

Hamburg), the

Minsk Ghetto became, in effect, a transit camp for those earmarked for

extermination. Most of the Jews from

Hamburg were transported directly

to Maly Trostinec (

Blagowschtschina) to be killed there.

In

April 1942,

Heydrich ordered

Eduard Strauch, the commander of the Security Police and Security Service in

White Ruthenia, to kill the deportees immediately on arrival. After the first phase of deportations to

Minsk had been concluded in

November 1941,

16 trains with more than 15,000 people from cities in the

Reich,

the "Protectorate", Poland, Austria and France arrived at the

Minsk goods station

between May and October 1942.

Starting on

10 May 1942, and continuing during the early morning hours (4 - 5 a.m.) on

Tuesdays and Fridays thereafter, most of the deportees were brought to the primitive "railway station" at

Maly Trostinec, which was sited at a dead-end railway track in the camp.

From

August 1942 onwards the trains were routed via a branch line much closer to

the estate itself, and from that time on it was here that disembarkation and selection took place.

The few not chosen for immediate

execution were formed into

Sonderkommandos, (special detachments). They were kept in the camp under

heavy guard, and forced to take the bodies of those killed to pits where they were buried or burned, to

sort out the effects of those who had been murdered for shipment back to Germany, or on camp maintenance.

From time to time these slave-labourers were subject to selection and murdered in their turn. In addition

to the shooting squads, four gas vans were in operation in the

Minsk area, some

of which began operating at Maly Trostinec at the

beginning of June 1942.

Known locally as "Dushegubki" ("soul killer" in Russian), they accounted for many victims.

|

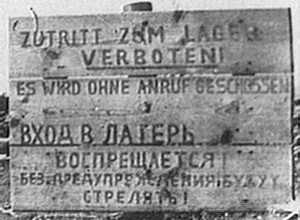

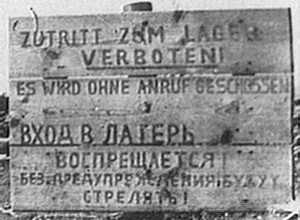

| Original Sign: Shooting without Warning! * |

Tens of thousands of Jews from Byelorussia, and other European countries were killed at Maly Trostinec.

Trainloads of Jews from Austria, Germany and the Czech Republic arrived and were exterminated. Transports

were organized in

Berlin, Hannover, Dortmund, Münster, Düsseldorf,

Köln, Frankfurt am Main, Kassel, Stuttgart, Nürnberg, München, Breslau, Königsberg, Wien,

Praha, Brno and

Terezin (Theresienstadt).

After the first transport left

Wien for Maly Trostinec on

6 May 1942, a further 8 transports containing

7,500 Viennese Jews followed, along with several hundred Austrians taken from

Terezin. Only 17 people are

known to have survived among the almost 9,000 Austrian Jews deported to Maly Trostinec.

Between 14 July 1942 and 22 September 1942, five transports, each containing

about 1,000 people, arrived at Maly Trostinec

from

Terezin. One of these transports left on

4 August.

40 deportees were removed from the train in

Minsk.

The remaining 960 Jews were ordered off the train, loaded into gas vans and driven into the forest.

Of 1,000 Jews in a further transport which left

Terezin on

25 August, 22 younger

men were taken to work on a farm; two of them escaped to join the partisans. One was killed in action. One

survived the war; all others in the transport were gassed.

A report, prepared for

Himmler on

23 March 1943 by

Richard Korherr of the SS statistical department, summarised

the number of Jews deported up to

31 December 1942 from the

Reich and the

"Protectorate" area: Germany 100,516, Austria 47,555, "Protectorate" 69,677; a total of 217,748. There were

to be further transports from Germany in

1943. Many of those transported in

1942 - 1943 from these countries were destined for Maly Trostinec, and death.

In

May 1943, approximately 5,000 people were held at the camp site. 500 victims

were liquidated every day, by use of gas vans, which went to and from

Minsk

and Maly Trostinec every day, carrying 75 people per journey.

In

August 1944, it was estimated that 40,000 foreign Jews had been

killed in the

Minsk Ghetto and its suburbs. More recent research suggests that

in Byelorussia as a whole, the Nazis murdered at least 55,000 Jews from the

Reich and the "Protectorate".

Maly Trostinec also served as a killing site for the Jews of

Minsk and the

surrounding area. Since Maly Trostinec was only one of several places where Jews were murdered in the

Minsk region, it is difficult to arrive at an accurate figure for the number

of Jews killed at the camp. There were about 400,000 Jews living in Eastern Byelorussia in

mid 1941.

Approximately 80%, or 320,000 Eastern Byelorussian Jews, were murdered during the occupation. Relatively

few were transported to the Polish death camps; most were killed on the spot. In addition, the Jewish pre-war

population of Eastern Byelorussia had been swollen by an influx of refugees from Poland, fleeing before the

German invaders.

But Jews were by no means the only victims. Many thousands of Byelorussian civilians, Byelorussian partisans

and, most of all, Soviet POWs were murdered at Maly Trostinec. Unlike the transports from the West, there

were no lists to record the number and identities of those killed. For this reason, and because the Germans

destroyed most of the records about the camp, as well as the obliteration by them of much of the physical

evidence, the estimated death-toll of the Maly Trostinec complex has varied enormously. Estimates place

the total number of victims at 206,000 (W. Benz: "Dimension des Völkermords", "Mordfelder"). In

1995, following

further examination of archival material, the number of those killed was revised upwards to 546,000, although this

figure may be taken to refer to the

Minsk area as a whole. For example,

between September 1941 and October 1943, mass shootings were carried out in the

Blagowshtchina forest, 5 km from Maly Trostinec, where an estimated number

of 150,000 people were killed, before the executions site was moved in

October 1943

to the

Shashkowa forest. Here more

than 50,000 people were murdered.

It should be stressed that many of these estimates of the numbers of victims are based upon

Soviet investigations organised in Minsk in

1944 - 1945. It is probable that the

actual number killed, either by shooting or in gas vans, was lower. The German historian, Christian Gerlach, has

calculated the total number of victims of Maly Trostinec at 60,000. What is indisputable is that Byelorussia

suffered the highest overall loss of life of any former Soviet Republic during WW2.

In

June 1942

Heinrich Himmler ordered

Paul Blobel

to erase all traces of the mass killings in the East.

Blobel formed the

Sonderkommando 1005 for the purpose of exhuming and burning the corpses of

those murdered. The first operations of

Sonderkommando 1005 in the Soviet Union began at the

end of September 1943 at

Babi Yar, outside

Kiev. Seven weeks were

allotted for conducting the

Sonderkommando 1005 operations in Byelorussia, with

disinterment and cremation beginning at Maly Trostinec on

27 October 1943. The camp

commander received police reinforcements as well as 100 Jews who were ordered to undertake the hideous task. The Jews

refused to do so and were immediately killed in gas vans. In their place, a group from the

Minsk prison was allocated, and promised freedom on completion of the work. Instead,

they too were gassed.

Whilst working, and at night in the bunker in which they were housed, they had been chained together in order

to prevent escape. This was common practice of

Sonderkommando 1005, wherever it operated. The

witnesses were to be destroyed along with the evidence. 34 mass graves (some up to 50 m long) in

Blagovshchina forest were opened, a number of which contained as many as

5,000 corpses. After the cremation of around 100,000 corpses was completed, a team of Soviet POWs were made

to sift the ashes in search of gold. The ashes were used as fertilizer for the camp fields.

|

Shaskowa Lake, where the

Gas Vans were cleaned * |

|

A Soviet Commission

inspects the pit in 1944 * |

A cremation facility was also built in

Shaskowa forest (500 m away from the camp)

in the

autumn of 1943, where

the bodies of those killed by shooting and gassing were incinerated. Here, from inception, the Germans tried

arranging an execution pit as a primitive crematorium. A 3 m high wooden fence was built around the site.

6 parallel rails (10 m long) were installed at the bottom of a 4 m deep pit, with an iron grate placed on them.

The pit was supported on three sides with iron panels. The fourth side served as a ramp where the gas vans unloaded

the bodies of the victims, directed by deputy Camp Commander

Rieder. The 30

workers who built the cremation facility, were then shot and burned in the pit. This cremation pit was visible

until the

1960's. A nearby lake served for cleaning the gas vans before they returned to

Minsk.

|

| Kolchos Barn: Cremated Victims * |

On

28 June 1944, as the advancing Red Army approached Maly Trostinec, Russian

airplanes attacked the camp.

That day, the camp guards (Latvian, Ukrainian, White Russian, Hungarian and Rumanian SS auxiliaries) were

replaced by a special SS detachment (Germans). This detachment locked all surviving prisoners in barracks.

These prisoners were Russian civilians and Jews from

Minsk and elsewhere. The

barracks were set on fire. The SS shot at all those who fled the blazing buildings.

About 20 Jews managed to evade the fire and the bullets;

they hid in the nearby forest until the arrival of the Red Army six days later. Amongst the few survivors of

Maly Trostinec, they were taken to

Moscow by their liberators and kept for

two years in a Siberian camp before being released in

1946.

On

28 or 29 June 1944, the chief of the

Sipo and SD in

Minsk,

Heinz Seetzen, ordered the execution of the remaining 6,500 prisoners in the

Wolodarski Street Prison and the

Schirokaja Street Camp in

Minsk.

Between 28 and 30 June 1944 they were locked in the former kolchos barn in Maly Trostinec,

then shot

and burned: The first victims had to stand on a layer of firewood, then they were shot. Their bodies were covered with

another layer of wood. Then the next victims had to climb on the pile and were shot. This went on until the last layer

of bodies reached the top of the barn. Three other funeral pyres were erected beside the barn, then the whole

apocalyptic arrangement was burned down. On

4 July 1944, 4 days after this action,

Soviet troops arrived at the site.

The burning pyres were still visible.

On

30 June 1944, the Germans had burned the remainder of the camp to the ground.

Witnesses' testimonies of mass murder at Maly Trostinec became available soon after the Red Army liberated

Minsk.

A resident of

Bolshoi Trostinec described how tractors had been used to level

the bodies in the burial pits

in order to enable further bodies to be buried at the same place. Another witness told how a group from

Minsk prison had been brought to Maly Trostinec as part of the

Sonderkommando 1005 operation. A member

of the SS described how 18,000 Jews from

Minsk had been murdered at the

end of July 1942. At that time, four

gas vans operated 24 hours a day, whilst other trucks were used to transport the victims to Maly Trostinec for

shooting.

In post-war trials, conducted in West Germany in connection with crimes committed at Maly Trostinec,

Otto Erich Drews, Otto Hugo Goldapp and Max Hermann Richard Krahner

were all sentenced to life imprisonment for their part in the killing of members of

Sonderkommando 1005. Others were given varying sentences in connection with war crimes carried out in the

Minsk area, including Maly Trostinec. A number of trials took place in

the Soviet Union. Overall, the number tried represented a small minority of the perpetrators.

Of all of the extermination sites in Poland and the former Soviet Union, perhaps least is known in the West

about Maly Trostinec. Unlike

Majdanek and

Auschwitz-Birkenau,

little physical evidence remained of the camp and there were few survivors. There was no overall command structure,

as existed in the

Aktion Reinhard camps, and thus a less organised pattern of crime. Insufficient research

has been conducted in the West into Maly Trostinec, yet those killed there may have been comparable in number to

the victims of

Majdanek or

Sobibor, and may possibly have been greater.

With increased access to previously classified Soviet and Eastern bloc documentation, it is to be hoped that this

anomaly will eventually be rectified.

Sources:

Hilberg, Raul.

The Destruction of the European Jews Yale University Press, New Haven 2003

Gilbert, Martin.

The Holocaust Collins, London 1986

Gutman, Israel, ed.

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust Macmillan Publishing Company, New York 1990

Epstein, Eric Joseph and Rosen, Philip.

Dictionary of the Holocaust Greenwood Press, Westport / Connecticut 1997

Poliakov, Leon.

Harvest of Hate: The Nazi Program for the Destruction of the Jews of Europe Syracuse University Press, 1956

Buscher, Frank.

Investigating Nazi Crimes in Byelorussia: Challenges and Lessons

Justiz und NS-Verbrechen

Gerlach, Christian. Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in

Weißrußland 1941-1944, Hamburg 1999

Kohl, Paul. Trostenez - Das Vernichtungslager bei Minsk In: "Existiert das Ghetto noch? Weißrußland:

Jüdisches Überleben gegen nationalsozialistische Herrschaft." Edited by Projektgruppe Belarus. Berlin-Hamburg-Göttingen 2003.

Langenheim, Henning. Mordfelder Elefanten Press, Berlin 1999

Photos:

Trostenez - Das Vernichtungslager bei Minsk - Official booklet from the

Belarussian State Museum of History of the Great Patriotic War

*

Mordfelder *

© ARC 2005